Alfred Lang | University of Bern, Switzerland |  |

Edited Book Chapter 1993 |

On the Knowledge in Things and Places | 1998.00 |

@EcoPersp @CuPsy @DwellTheo |

32 / 37KB Last revised 98.11.14 |

Pp. 76-83 in: Mario von Cranach; Willem Doise & Gabriel Mugny (Eds.) Social representations and the social basis of knowledge. Swiss Monographs in Psychology Vol. 1. Bern, Huber, 1992. | © 1998 by Alfred Lang |

info@langpapers.org |

Scientific and educational use permitted |

Home || |

Inhalt

Zusammenfassung / Abstract Why do we make things and places?

Dialogue of a young man with things in his room

An eco-semiotic perspective on persons and their environment

References

Zusammenfassung

Über das Wissen in den Dingen und

Orten. Wir pflegen davon auszugehen, dass das psychologisch

interessierende Wissen in den Köpfen der Menschen liegt,

während das extern in strukturiertem Raum, gestalteten Dingen,

in Schrift und Bild gespeicherte Wissen der Gegenstand anderer

Wissenschaften, der Kulturwissenschaften, darstellt. Der Beitrag

untersucht in strukturaler und funktionaler Hinsicht Gründe

dafür, dass diese Trennung mit einiger Willkür verbunden

ist, und skizziert eine alternative Konzeption. Anhand eines

Beispiels wird die Handlungsrelevanz externalisierten Wissens oder

externaler Erkenntnisstrukturen aufgezeigt und eine psychologische

Interpretation der Semiotik bezogen auf Mensch-Umwelt-Transaktionen

oder ökologische Einheiten vorgeschlagen.

Abstract

On the knowledge in things and places. We

have a habit of assuming that psychologically interesting knowledge

is in the head, while knowledge stored externally in the structure of

places, the design of things, as well as in pictures and scripts is

given over to other, cultural, sciences. This contribution reasons on

structural and functional levels for the arbitrariness of this

separation and sketches an alternative conception. With the help of

an example, the relevance of externalized knowledge or external

cognitive structures for acting is demonstrated. In addition, a

psychological interpretation of semiotics is proposed to deal with

men-environment-transactions or ecological units.

Inhalt

Why

do we make things and places?

It is the contention of psychology in

general that some dynamic structure within living beings is

both the resultant as well as the foundation of any

process or state called psychological. In particular, every instance

of what an individual ever sees, hears, feels, thinks, acts, etc. has

a potential of leaving some trace or becoming incorporated in its

peculiar way into the psychological organization of that individual.

And it is this psychological organization within the

individual which in turn determines or codetermines both any further

perception or action as well as further internal states or processes

of that individual. In fact we all assume that nothing psychological

ever happens without the (internal) psychological

organization. We call it the psyche, the mind, the content of the

psychological blackbox or the cognitive structure: strange indeed

that psychologists have never found it worthwile to agree on a single

term in order to designate that most fundamental construct of their

science.

However, most, if not all, of what people do

also has a potential of leaving a trace in the real surroundings

of the actor or of becoming incorporated in a peculiar way into

the (external) environment of the actor. Be it in a more

transient or in more durable way, many of our activities tend to

change some aspect of the world, as it exists then independently of

their originator.

In turn, this modified environment then

has a potential of influencing our further perceptions and

actions, those of the originator of the change as well as those

of many other individuals. Again we are all inclined to agree that

such transformations of the external world are in some way the

effects of the psychological organization of the acting

individual. And we also agree that behavior and experience of persons

is in some way influenced by the situations and events thus

created. In fact this is the central thesis of (trans-)action

theories. However we do not usually combine the two principles of

internal and of external organization into a single coherent

construction.

Indeed, also the external environment

functions both as a resultant and as a foundation of most

processes or states called psychological. Yet effects of behavior,

i.e. changes of the world brought about by behavior of persons, are

considered not to be psychological in nature. They are generally

taken to be objective facts and they do not interest psychologists in

any other way than that they can be indicative of psychological

processes (responses), or that some of them might eventually play a

role as (co-)determinants of other psychological processes (stimuli).

However, behavioral effects of the actions of many persons over time,

taken in their totality as human culture, are an organized whole of

meaning quite comparable to the mind in richness and differentiation

and perhaps also in their power to incite and to control

behavior.

The traditional separation of the world into

the objective or material and the subjective or psychological is

apparently self-evident; however, it is not a matter of fact but

rather a particular conception or construction of the world. It

should be pinpointed as Cartesian dualism, common in Western

civilization of the last few centuries. The above examples of mutual

effects between "the psychological" and "the material" call for an

interactive dualism. Yet most modern psychologists confess to

epiphenomenalism which is an asymmetric dualism that accepts

body-to-mind sequels, such as from brain to conscious experience, but

denies mind-to-body causation. The latter, however, obviously is

factual when we think of the consequences on the material world of so

many evaluations, plans or decisions which are undoubtedly mental.

The preferred solution today is to retreat to monistic

materialism which in turn disallows psychology a separate

existence.

Psychologists, so it seems, have carefully

avoided dealing with the outgoing branch of the mind-body-problem,

although over the centuries a large body of speculation has been

directed towards the assumed dependencies of the subjective on the

objective. Fechner has posed the psychophysical problem in terms of

the psychological being a function of the physical. The program has

failed, although variants thereof are still pursued. And the

reactive image of man proposed by psychophysics remains to

reign over this science. It is obviously conterintuitive. It is

incompatible with everybody's daily experience of being a subject,

i.e. of being a person capable of deciding and acting, at least

within certain restrictions, on the basis of one's own "free will".

It is true that important portions of the world surrounding living

beings have their characters independent of those subjects. Yet

particularly for any human being, most entities, particularly the

important ones in everyday life, are the result of human action, of

action by the person in question as well as by others. It is human

culture, evolved in many particular versions over many

generations and supplemented and modified every moment, that is

the preeminent determinant of human existence. No psychologist

has ever formulated a program complementary to Fechner's

psychophysics, i.e. to understand artifacts as a function of the

mental. But the fact is that our civilization has simply acted that

way: man as a measure for all things; and is on the verge of

destroying living conditions.

Psychology, in a way then, has forbidden

itself half of its potential subject matter. On becoming an empirical

science, it has restricted its endeavor to a cause-effect way of

looking at the world of people. Causes are assumed to be givens, they

are thought to have effects on people. The business of psychology is

understood to find out how these effects on people are brought about.

Yet culture is not adequately described as an aggregation of stimuli.

The objective is not simply the material, nor is

the subjective well enough captured by subsuming it as the

mental. Probably, the reverse type of psychophysics would be

as much deemed to failure as the traditional one. What is needed is

at least a bi-directional or transactional view of the ecological

relation or, better still, a conception beyond Cartesian dualism. We

live in a world of things and places, i.e. objects and spaces that

carry meaning. And things and places form an ordered system which

obeys both natural laws and psychosocial determinants.

In a related chapter entitled "The 'concrete

mind' heuristic: human identity and social compound from things and

buildings" (Lang in press a), I have proposed to give up the

venerated separation of the world into the material and the

immaterial. As much meaning is "stored" and is available for any

individual being in her environment as in his brain. An action or a

developmental change of an individual are often and vigorously

incited by external structures or processes which have been built up

or prepared by the actor himself or by other members of a smaller or

larger cultural group. Actions can be controlled by external

entities, as much as they are from within.

In fact, the mind as a complex and dynamic

structure in continuous change is no less material in character than

the totality of the cultural forms incorporated in the objects and

spaces of our surrounds is mental, and vice versa, because both

incorporate or carry, by means of physical formations, an

organization of meaning which is always both, objective and

subjective.

In addition, both of these structures, each

considered in its own right, are genuine nonentities from a

psychological point of view. The internal mind would be empty, if it

could not represent the environment of the individual in question;

and the cultural environment would be nil, if it were not produced

and maintained by people. Human individuals of all societies, if

deprived of their material belongings, from clothes to furniture or

from tools to houses, would be at pains to acquire and maintain their

personal identity. And a human society devoid of common material and

symbolic structures from territories to signs of dominance or

autonomy, from objects for exchange to cosmic myths, is simply

incomprehensible. There must be causes for animals and humans to

turn spatio-temporal formations into carriers of meaning. Common

answers to this question are mostly precipitate and all too often of

an arbitrary "for-this-and-that"-nature. Reasons are not enough. My

contention is that the authentic preconditions for things and places

are of an essentially psychological nature and that the answer

is not completely different from that of explaining the evolution of

the mind/brain.

External memory or the "concrete

mind" is then a formula I have chosen as a catch phrase to point

to the functional equivalence of the (internal) mind and the cultural

environment. There is a large thesaurus of knowledge stored in the

spaces and objects formed and cultivated by people. If we want to

understand it, we have to study people in conjunction with these

external structures. Men-environment-systems or ecological

units are in my opinion the proper subject of investigation for

psychology in an ecological perspective. Such systems are found on a

scale ranging from the petty things of everyday settings to

dwellings, neighborhoods, cities, institutional settings of all kinds

to culture in its entirety.

Inhalt

Dialogue

of a young man with things in his room

In the following section, a pilot study is

briefly summarized which has been directed at understanding

person-thing-relationships in the context of private rooms. Credit

and thanks for the study go to Silvia Famos (1989) who did it under

my direction as a Diplomarbeit. The method used combines a

survey of (arti)facts and their topography in the present and in the

former private room with a structured interview about the personal

history of five important things in the rooms of four young men.

Facts and transcripts have been grouped and interpreted in the form

of parallel case studies. This method, of course, is a provisional

one, because it is restricted to reflections on objects and people;

it will have to be supplemented by methods directed at

person-environment-systems in transactional development. Theoretical

guidelines are gathered from the symbolic action theory of

Ernst Boesch (1980, 1982, 1983, 1989), the psycho-sociological study

on the meaning of things by Csikszentmihalyi &

Rochberg-Halton (1981) and the author's regulation theory of

dwelling activity (Lang 1987, 1988, in press

a).

The study illustrates that objects important

for a person are placed at non-arbitrary points within a room and in

relation to each other. Placement and the resulting thing-topography

is only partially determined by the functions or the outside features

of the objects, they are rather part and parcel of a complex ensemble

of meaning which is most readily made explicit in terms of

psychosocial identity of the person involved. Although most of

the things picked by the person as "special" are functionally passive

objects, they enter a thing-person dialectic which can only be

understood in a developmental perspective. The relative placements of

the things is subject to subtle changes, and so does the relationship

between the things and the person.

Although our material is, in the main,

verbally communicated, it is apparent that much of the meaning of

these things and their topography is not primarily of a planned

character, nor is all of it spontaneously conscious. In the process

of talking about these objects the persons involved are repeatedly

surprised and amazed on the rich network of relations connecting

their things with their room in a system of meaning. Indeed, much

more is known to the person than they can and do talk about; but

repeatedly new facets or new ways of understanding surface with the

intensive engagement with these ordinary, everday, self-evident

matters of course.

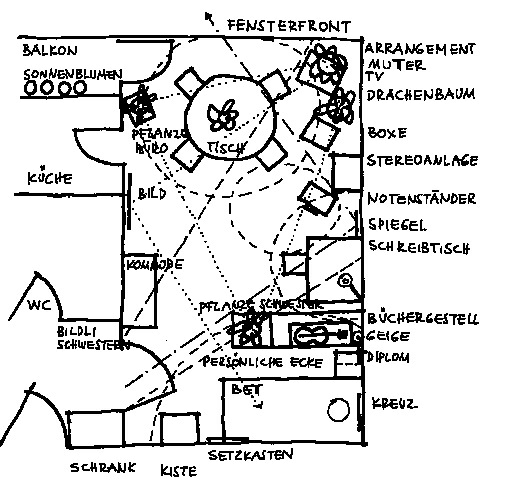

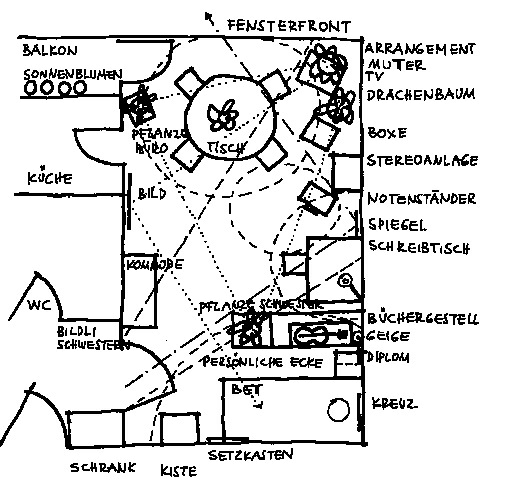

Fig. 1 a. Floor plan and important things in

the present room of B.

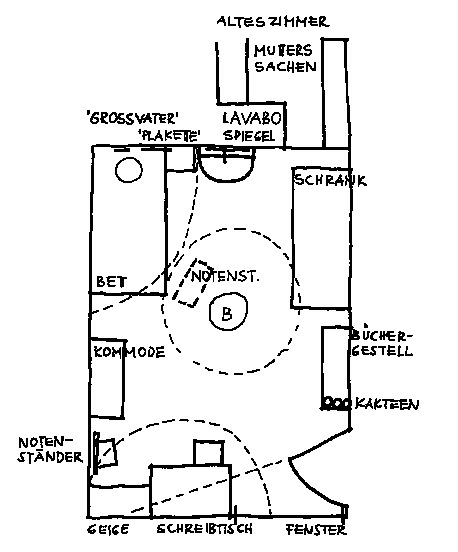

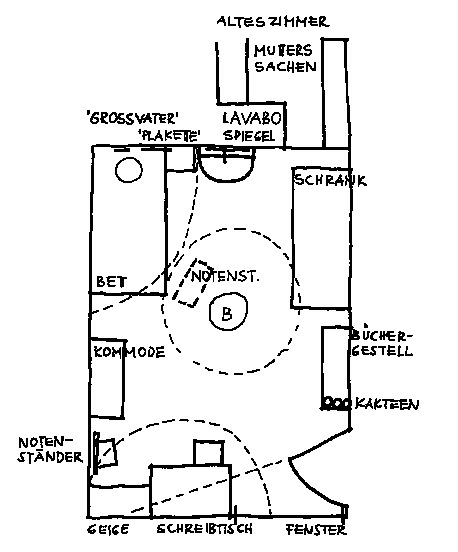

Fig. 1 b. Floor plan and important things in

the former room of B.

In an attempt to relate here some insights

into the essence of the study, one of the cases (B) in Famos (1989)

is briefly summarized and illustrated in Fig. 1.

B is a 25 year old machine construction

engineer who also semi-professionally plays the violin in an

orchestra and in a string quartet. After the recent death of his

mother he moved from the parental home (Fig. 1a, former room) to a

one-room apartment in another city, but in the vicinity of one of his

two older sisters (Fig. 1b, present room). He is described as a

good-natured and joyful person with an open mind, but socially

well-mannered and rather cautious. A penchant for religious,

naturistic or artistic experience dominates over social interests,

although he can be an ardent debater of topics of interest to him.

The five things chosen to talk about

by B are: the violin, the bed, his plants, a picture and a crucifix.

In the following, in order to be brief, data and interpretation

cannot be separated in a desirable manner. Obviously, in both rooms

the violin takes a particular place near the bed in a most

personal corner. While it has taken the central floor (note stand) in

the former room, at present it seems more integrated, both with

musical equipment and with other professional and social items.

Violin playing has been and is an important vehicle for finding

personal identity for B; although not by family tradition a musical

milieu, B's father induced and supported this interest. B has long

considered a professional career but has recently settled for a high

amateur level and sees his music in a complementary, rather than in

the former competitive relation to his engineering talents and

activities.

The bed is an important place in the

room for B. As a slightly closed off space behind the entrance, it

affords rest, regeneration, security; as an object with family

history, it also reminds one of the continuity of generations.

Plants have always fascinated B, but in his parental home,

house plants were cared for by his mother, while B pursued his almost

religious relation with nature preferably outdoors. After her death,

and in his new room, he has developed his small set of cactuses to a

rich collection of different plants spreading over large parts of the

room. On the pretext of asking for her advice and help, the plants

also help carry B's relation with his sister.

Both the picture and the crucifix are recent

additions. The placement of the crucifix is an intentional

and "displayed" effort to confess his spiritual engagement and, at

the same time, somewhat paradoxically, to cultivate relations with

religious family ancestors as well as to confirm religious attitude

and find distance to the church as an institution. The picture,

on the other hand, seems primarily to be a private dialogue of B

with himself. Apart from the admission that the picture must have

originated out of a mental constellation similar to his own, B only

reluctantly and indirectly talked about details; from the facts that

it is actually a photograf of a painting by an absent friend, showing

a sleeping pair in a somehow spheric setting, and from the confession

that B has selected it because of its content rather than its

artistic value, one can conclude that B alludes to and reminds

himself of his life situation as a somewhat solitary young man in

search of personal relationship. An additional remark on the social

functions of the rather big round table supports this line of

interpretation.

Seen as carriers of meaning, each of the 5

things thus refers to one of the paramount domains of B's

personal constitution and actual preoccupations: home base (bed) and

fulfillment (violin) seem securely settled in the room, whereas the

social (plants), partnership (picture) and spiritual (crucifix)

yearnings for belonging each take their separate section of the room.

In addition, these domains together form an ensemble of

relationships which, especially when considered in their development,

do not appear random nor entirely determined by functions or room

architecture. While, for example, in the former room the home base

(bed) was found at the far end, at present it is near the entrance;

yet in both situations it is protected from immediate intrusion by

the opening door. Items referring to personal and social relations,

as good as absent in the parental home room, now nearly mushroom in

the upper left half of the room; they appear to represent both

factual and hopeful associations, the former mostly to kinspeople,

the latter oriented towards deep and personal relations.

This short summary of one case cannot give

more than a crude illustration of our contention that things are more

than objects. Evidently, methodology and theory have to be elaborated

in conjunction.

Inhalt

An

eco-semiotic perspective on persons and their

environment

The main purpose of the present pilot study

was to help sharpen conceptual tools with the objective of an

improved methodology. The last section therefore is a brief attempt

to elaborate a conceptual perspective for dealing with ecological

questions such as those in the above example.

Two markers can be used to characterize this

approach: (a) it investigates men-environment-systems or

ecological units in evolution; (b) it applies triadic

semiotics as a conceptual tool for description and explanation of

psychological process and structure.

Enough has been said in the first section on

(a) and it should also be clear by now that our approach to persons

in their environments is neither materialistic nor

mentalistic. Psychology on the whole is no great success and

probably cannot gain on one of the traditional platforms, be it

behavioristic or cognitivistic. I propose semiotics in the tradition

of Charles S. Peirce as a candidate for a new platform, because as

a general logic of representation it perfectly fits the

ecological problem. I hope to give more than the present sketchy

impression elsewhere.

In semiosis, understood as a general

logic, something stands for something to somebody. Semiosis,

understood as a process, describes the encounter between two

entities from which a third entity results. Semiotic terminology, and

sometimes also conceptions, unfortunately are rather variable. Let me

use the term referent (object, source etc.) for the first or

originating entity, interpretant (subject, agent, etc.) for

the second or mediating instance, and representant (sign

proper or in the narrow sense, sign carrier etc.) for the third

entity resulting from the process. The psychological interpretation

of semiotics proposed here thus, in some way, deviates from the

Peircean conceptions of interpretant and representant; here is not

the place to give the reasons.

We have seen that a person selects and

places furniture and related items in a particular ensemble. And we

have tried to understand these actions as a result of a particular

constellation of a given person and his social and cultural

environment in a certain stage of joint evolution. In general then,

we conceive of a system of separate but interrelated parts, some of

them individual and social beings, some of them objects and spaces

with certain physical, spatial, temporal, functional, formal etc.

characteristics. In semiotics, every single entity that can be

differentiated against others and that is also capable of entering a

relationship with some other entity, can become a sign.

On the surface, semiosis or the

sign-process is the process of using and producing such signs.

Through semiosis sign-structures are created by some agent on the

basis of sign-structures. Functionally, semiosis is a triadic

representational logic that relates a referent to a

representant by mediation of an interpretant.

In the present psychological context, the

interpretant can be a person or any subsystem thereof. Seen

from the outside by the researcher for instance, the person is of

course the referent of the researchers semiosis and also a sign, viz.

the representant of a highly complex and lengthy sign-process.

Signs proper, i.e. representants, as well as referents are

always physical structures that carry meaning. There is no

meaning without a physical carrier; even the most abstract idea must

be incorporated somewhere and sometime, be it in a brain structure or

process or in a linguistic structure, spoken or written (see Lang in

press b). Otherwise it cannot become a component of semiosis

and is without effect or nonexistant. Hardly any physical structure

is without meaning as soon as it enters a semiotic relation and thus

automatically produces a representant for that interpretant; but it

has no meaning as such. Signs are always incorporating aspects

from both their referent and their interpretant. To describe a

sign, it is meaningless to give nothing but the specifics of its

physical properties; you have to include its referent as well as its

interpretant, because any given object can get various representants

for different interpretants and thus also may incorporate different

referents.

In a psychological interpretation of

semiotics, perception as well as action are considered

indeed prototypical sign-processes. Both build

(sign-)structures that refer, for the particular perceiver or actor,

to other (sign-)structures. Perceptions or intro-semioses build them

in the brain, actions or extro-semioses in the world; perceptions

have their referents in the world, actions in brain structures. And

since any sign proper or representant can become the referent of

another semiosis, a psychological interpretation of semiotics seems

to fit the known facts about people in their environment particularly

well.

We also might conceive of inner-brain neural

or humoral processes in semiotic terms. Thinking or feeling,

conscious or unsconscious "mental" streams or states could in

principle be understood as chains or nets of semioses. But we know

nothing directly about the respective sign-structures used as

referents and formed as representants in the brain/mind, except when

some of them serve as referents in additional semioses resulting in

external (verbal or behavioral) referents. I propose therefore to

concentrate on those sign processes that result particularly from

encounters between persons and their surrounding world, i.e. the

ecological semioses. An eco-semiotic approach to

person-environment-systems thus is an attempt to treat

structure-formation processes within the person and some

structure-formation processes outside in similar terms, and thus to

emphasize the functional equivalence of sign-processes originating in

the mind with those based on things and places (Lang in press

a and b).

An important advantage of a semiotic

conception of the ecological relation is that there is no need to

make any one of the two partners completely dependent on the other.

One need not assume that an animal incorporates nothing but the

natural laws that govern the surrounding world. Vice versa, man's

rationality is not self-sufficient and limitless. In addition,

representants, in semiotic parlance, are to be sharply

distinguished from the common idea of (symbolic) representations

of something, because the latter are dyadic, the former include a

triadic relation. The question of whether a representant is a true or

false representation of a referent is meaningless in a semiotic

perspective, except when a particular interpretant is specified. This

is not to say that sign systems would not vary in ecological

efficiency or pragmatic value.

Of course, semioses occur in never ending

chains or nets including circular references. Every representant

which is a component of one semiosis can become the referent in

another. Any given sign-structure stands at the apex of a double

"pyramid" of semioses extendend in time. It has on the one hand a

history of preceeding semioses, all of which have contributed in

various ways to the coming into existence of the given sign. At the

same time the sign-structure considered is also at the root of a

similar tree of semioses spreading into the future; and this, of

course pertains to any sign-structure.

It is meaningful then to investigate the

chaining of semioses; the minimal target is a pair of succeeding

semioses. Whereas psychology has interested itself in certain aspects

of the chaining of a perceptive or intro-semiosis

followed by an extro- or behavioral semiosis, it has,

except in some fields of social psychology, neglected the pairing of

an extro-semiosis followed by an intro-semiosis. One could say that

in the former case, the world "speaks" to itself by mediation of a

living agent. In the second case, a person "speaks" to themself or to

other persons by external channels and using messages carried by

objects with their potential of representants to become referents.

The latter then points to the fact that communicative acts in a very

general sense presuppose two chained semioses.

Such considerations lead to the feasibility

of semiotically understanding a person's intercourse with places

and things and thus going beyond the specific material, formal or

functional features of a given object or space. As a part of a

sign-process a representant turned referent might carry a general

communicative function. In a study by Daniel Slongo (in prep.)

it has proven useful to interpret things and places in the home in

terms of six general sign-functions; they have been defined in

reference to Karl Bühler and Roman Jacobson and are briefly

described in the following paragraphs.

Relatively few things in a room, so it seems

in a certain contrast to linguistic communication, become a component

of a sign process exclusively by their notative or referential

function as pointed out by Bühler. Nevertheless, in many rooms

we could identify things that in a way stand for or symbolically

represent some other persons to the inhabitant or to some of her

visitors. Much more prevalent are appellative and

expressive functions of things: chairs invite one to sit down,

plants or pets call for regular attention etc.; and many items

including decorations, pictures, trinkets, plants etc. placed in neat

or sloppy arrangements tell something about their owner.

Preliminary evaluations of the data in the

study by Slongo in addition reveal a rather important role of what

Jacobson called the phatic function of things and places. It

is common-sense that things and their arrangements contribute to

create atmosphere; but it is an open task to understand how this is

brought about, under what circumstances it works, and how recipients

of these messages are affected. Furthermore, a reflexive (or

metacommunicative) and an autonomous (or esthetic, poetic)

sign function could be distinguished.

In fact no systematic surveys of these

functions of household items are available. Csikszentmihalyi &

Rochberg-Halton (1981) have sampled the field and also placed the

cultivation of things in the context of personal and social

identity. Although they interpret their social meaning, they have

classified things mostly by their use rather than by their

communicative function. Investigations into the psychological

process of interacting with and by things and places are

wanting.

Inhalt

References

This chapter is a major rewrite of the paper presented at the

congress in September 1989. Some of the theoretical considerations

presented at the meeting have been elaborated in Lang (in press

a), the empirical material has been enhanced, and a sketch of

an outlook into further developments of the approach has been added.

The author gratefully acknoledges the active cooperation of Daniel

Slongo who is actually engaged in elaborating the conception of

things as "concrete mind" in his thesis work.

References to Peirce, Bühler and Jakobson have been omitted,

since they can be found in major reference books, e.g. in Nöth

1985.

Boesch, Ernst E. (1980) Kultur und Handlung: Einführung in

die Kulturpsychologie. Bern: Huber. (270 pp.)

Boesch, Ernst E. (1982) Das persönliche Objekt. In: E.D.

Lantermann (Ed.) Wechselwirkungen: Psychologische Analysen der

Mensch-Umwelt-Beziehung. Göttingen: Hogrefe

Boesch, Ernst E. (1983) Das Magische und das Schöne: zur

Symbolik von Objekten und Handlungen. Stuttgart-BadCannstatt:

Frommann-Holzboog. (335 pp.)

Boesch, Ernst E. (1989/90) Symbolic action theory for cultural

psychology (Provisional Draft 1989/90). Saarbrücken, by the

author (to be published 1991 by Springer in Berlin).

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihalyi & Rochberg-Halton, Eugene (1981)

The meaning of things -- domestic symbols and the self.

Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press

Famos, Sylvia (1989) Dialog junger Menschen mit Dingen im Zimmer:

Bedeutung und Topographie wichtiger Objekte im Lebenszusammenhang.

Diplomarbeit, Seminar für Angewandte Psychologie

Zürich.

Slongo, Daniel (1991) Zeige mir, wie du wohnst, ... -- eine

Begrifflichkeit über externe psychologische Strukturen anhand

von Gesprächen über Dinge im Wohnbereich. Diplomarbeit,

Psychologisches Institut der Universität Bern.

Lang, Alfred.; Bühlmann, Kilian & Oberli, Eric (1987)

Gemeinschaft und Vereinsamung im strukturierten Raum: psychologische

Architekturkritik am Beispiel Altersheim. Schweizerische

Zeitschrift für Psychologie 46 (3/4) 277-289.

Lang, Alfred (1988) Die kopernikanische Wende steht in der

Psychologie noch aus! - Hinweise auf eine ökologische

Entwicklungspsychologie. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für

Psychologie 47 (2/3) 93-108.

Lang, Alfred (in press, 1991) The "concrete mind" heuristic --

human identity and social compound from things and buildings. Pp.

xx-xx in: C. Jaeger; M. Nauser & D. Steiner (Eds.) Human

ecoloty: an integrative approach to environmental problems.

London: Routledge.

Lang, Alfred (1991) Was ich von Kurt Lewin gelernt habe. In: K.

Grawe et al. (Eds.) Über die richtige Art, Psychologie zu

betreiben. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Nöth, Winfried (1985) Handbuch der Semiotik.

Stuttgart: Metzler.

Inhalt

| Top of Page